As history has shown time and time again, when publishers apply pressure on developers, it usually results in lesser games. When a publisher primarily concerned with quarterly financials meddles determinedly in the development process, the game ends up either crippled, released far too early or bloated with unnecessary features incongruously shoehorned in to conform to current trends.

(“A chess game would be okay. But a chess game in HD played with a gimmicky controller, that’s what the world needs right now. Also, can we make it an MMO? And be on Facebook? With DLC?”)

However, UFO: Enemy Unknown a.k.a. X-COM: UFO Defense is an outstanding example of a game that benefitted immensely from publisher meddling.

The story goes Mythos Games’ Julian Gollop had trouble selling the initial Laser Squad-inspired design to Microprose, the game’s eventual publisher. Microprose had hit big with deep strategy games like Railroad Tycoon in 1990 and Civilization in 1991, and requested changes to X-COM’s design to make the game more Microprose-like. This would result in a game that is much greater than the sum of its parts.

If X-COM had been released purely as a Laser Squad-esque turn-based tactics game, it would still have been quite good. Julian Gollop had years of experience designing multiple turn-based games and as a result, X-COM’s Battlescape is one of the finest battlefield systems ever produced. Fog of war, line of sight, destructible environments, opportunity fire and morale all combine to create a superlative gaming experience that remains enjoyable 16 years after it was first released.

Tactics matter in this game. Running and gunning through the battlefield would almost always end disastrously, and the player will quickly come to appreciate the importance of cover, smoke screens, reconnaissance and bounding overwatch.

The destructible environments, aside from delighting those who simply enjoy blowing shit up, allowed improvised manoeuvres. The crafty player could explosively make his own entrance into a building to flank an alien lying in ambush by the door or create a shortcut to rush to the aid of a vulnerable squad member.

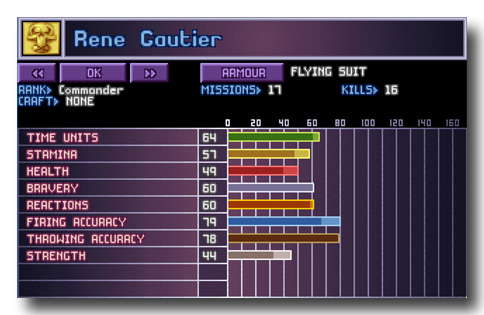

X-COM’s soldiers were far from being expendable resources to be casually tossed into the meat grinder of battle, and the player had every reason to keep losses to a bare minimum. A rookie soldier may be the first to be ordered into a UFO or the first to cross a wide open space but as he gained experience, he gained combat skill and nerves of steel, making him an invaluable squad member worth supporting and keeping alive.

Death, when it inevitably came, could have serious consequences both on and off the battlefield.

Unit morale was an important factor during Battlescape encounters. Heads would go down whenever a squad member fell in combat and multiple deaths within a short period time could cause complete loss of unit cohesion. Panic-stricken soldiers might freeze, run away or more dangerously, begin spraying shots wildly in all directions.

Defeats and even Pyrrhic victories might lead financial backers to lose faith and reduce funding, complicating efforts to recruit and equip replacements, making future missions considerably harder.

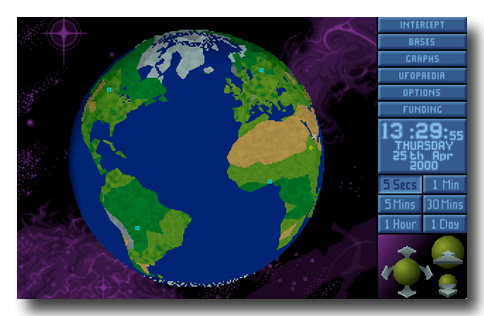

The real-time strategic layer, based on the Geoscape part of the game, is equally engrossing. Like legendary Microprose titles Railroad Tycoon and Civilization before it, X-COM is all about giving the player interesting decisions to make throughout a lengthy campaign.

With time and resources being limited, the player must constantly juggle priorities. Should funds be allocated for building new bases or improving the defences of existing ones? How should research and manufacturing be prioritised? Should UFO interception take precedence over the survivability of X-COM squads?

The decisions made at the Geoscape level affect the Battlescape missions and Battlescape mission outcomes affect the Geoscape strategy. It is this synergy of the two disparate aspects of X-COM, the turn-based Battlescape and the real-time Geoscape, that makes it a brilliant game.

And it was the synergy of developer and publisher that made this possible. Indeed, this game represents the perfect confluence of developer and publisher since neither party could have created it on their own. Microprose attempted to do so with the sequel, Terror from the Deep, and stumbled. Julian Gollop’s post-X-COM designs were smaller in ambition and scope, and his attempts to develop a spiritual successor to X-COM were aborted by faithless publishers. Other developers have tried to recapture the X-COM magic and fallen short.

Of course, it would be irrational to suggest it is impossible to recapture the game’s magic. Somewhere out there is a developer who understands what makes X-COM tick, what makes it the legend it is, and perhaps somewhere out there, too, is a publisher willing to take a chance and provide the kind of support a great game deserves.